All about A/B tests

I recently read what is likely the most popular book on A/B testing - A / B Testing: The Most Powerful Way to Turn Clicks Into Customers. The authors provide an excellent overview of the potential of A/B tests for products spanning across various online domains. The book is full of great examples of successes (and failures) of applying A/B testing - it’s a quick and easy read too. The current post is my take on the steps involved in conducting a successful A/B test. While conceptually A/B tests are simple, they can be a huge number of nuances that come up in practice.

Definition

The basic concept of A/B test is essentially the underpinnings of the scientific method (its original roots are from early 20th century from the agriculture industry). Most scientific researchers are performing A/B testing, while only a subset of them use the term. From Wikipedia -

A/B testing is a way to compare two versions of a single variable, typically by testing a subject’s response to variant A against variant B, and determining which of the two variants is more effective.

A/B testing is also called randomized control trials in the context of medical/drug testing.

Steps in A/B testing

In the business world, A/B testing is the culmination of statistics, hypothesis testing, experimental design, engineering and business intuition. With so many moving pieces at play when designing an A/B test, it is important that our approach be structured to maximize our chances of success. Adopting a well-established set of rules avoids arriving at premature (or wrong) conclusions. The following are guidelines generally agreed to be best practices. We will consider the example of a audio streaming platform that is considering a discount to its users to encourage more subscriptions.

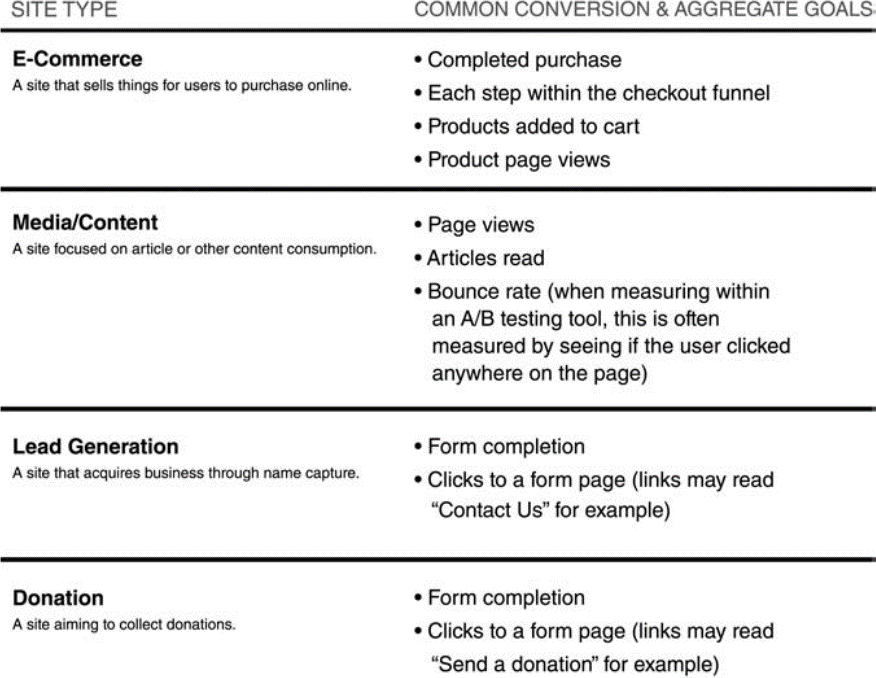

- Define your success metric (aka what are you optimizing for?) - It is important to establish our success metrics early on in the pipeline. The authors in the aforementioned book mention that it is important to ‘crystallize our raison d etre’. However, defining these metrics is not always straightforward. In our above example, it is likely that we care more about increasing our profits in the upcoming months more than we care about adding subscriptions in the short term. There is a possibility that more users subscribe because of the discount but not nearly enough to justify the loss in revenue that we incur from the discount. There are also distinctions made between macroconversions, microconversions and other vanity metrics. Imagine that running this promotion attracts more free users of the platform (in addition to subscribers), which might be beneficial in the long run - this is called microconversion. Another important point to consider is - what stage is our company in? Revenue and profits are not as important for an early stage company where the primary goal would be to build a user base. It is crucial to keep the success metrics quantifiable (at least within the context of the A/B testing framework). Following is a list of suggested metrics by Dan and Pete -

For our problem above, we will assume that the goal is an increase in revenue.

- Construct a hypothesis - Identify areas for potential improvement of the platform or service. In our example above, our hypothesis is that providing a discount to some of the users of the streaming platform increases subscriptions. More formally: \( H_0 \) = no increase in subscriptions after discount \( H_a \) = some (predetermined value) increase in subscriptions after discount

- Determine intended lift - In statistics and experimental design domains, lift is the measure of the performance of a modified model in having an enhanced response as compared to a baseline setup. In simpler terms, lift is the measure of how much better our new setup performs (or is intended to perform) in comparison to our existing setup. In the context of the above example, we determine lift by asking the question - ‘how much increase in revenue do we aim for?’. The answer to this question again depends on a lot of factors:

- how saturated is the market - we can aim for higher lifts in markets that are not saturated.

- the company culture - some companies are inherently setup to be more innovative - such companies tend to aim for higher lifts.

- how big our user base is - if our platform has a million daily users, even a small lift is beneficial. FAANG companies, for instance, aim for 1% lifts.

- An excerpt from Dan and Pete’s book that is relevant here: One of the things that we like to tell companies that we work with is to be willing to think big. Being too complacent about the status quo can lead to focusing too much on fine-tuning.

- Perform power analysis to calculate sample size - The goal from a statistics standpoint is to reach statistical significance, and reduce the probability of making errors. Setting up the sample size for an experiment involves the following quantities:

- The significance level (\( \alpha \)) - by definition, \( \alpha \) is the probability of making a type I error. Or, the probability of false positives. This level is generally taken to be 0.05.

- Statistical power (\( 1-\beta \)) - \( \beta \) is the probability of making a type II error, that is the probability of false negatives. Statistical power is the complement of \(\beta \) - we usually prefer power to be 80% or higher, although in practice, power is much lower.

- The effect size - This is analogous to lift described earlier. Higher the intended effect size, lower the required number of samples in the two experimental groups. There are also other means of quantifying effect size - Cohen’s d is a standard metric.

- The sample size - The sample size required to achieve statistically significant results depend on the above factors mentioned. The general expression for calculating the sample size is as follows \(Sample size = \frac{z_{score}*\sigma*(1-\sigma)}{MOE^2} \) Where, MOE is the margin of error. In practice, however, we write some simple code to calculate the sample sizes (or use an online calculator).

The above gives the following output:

Sample Size: 1571

Going back to our streaming service example above, let’s assume that the baseline conversion rate was 5% - which means that 5% of the users of the free app converted to the subscription service. Now, our intention is to increase this to 6%. We will keep the default values of \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) as above. The resulting sample size is 7663 per group. This means that we have to randomly assign 7663 users to see the discount and compare their conversion rate with that of the baseline user (without the discount).

- Run the experiment - Once we have figured out the number of samples required in the experiment and controlled groups, we have to run the experiment. It is obviously important to ensure that the two groups are randomly selected and no bias is introduced. In the above example, for instance, if we roll out all the discounts on a Monday afternoon, our results will be biased. Also, in this step, it is recommended that one does not peek at the results before reaching the required sample size, partly because we can trick ourselves into thinking that a considerable effect is present when there is none.

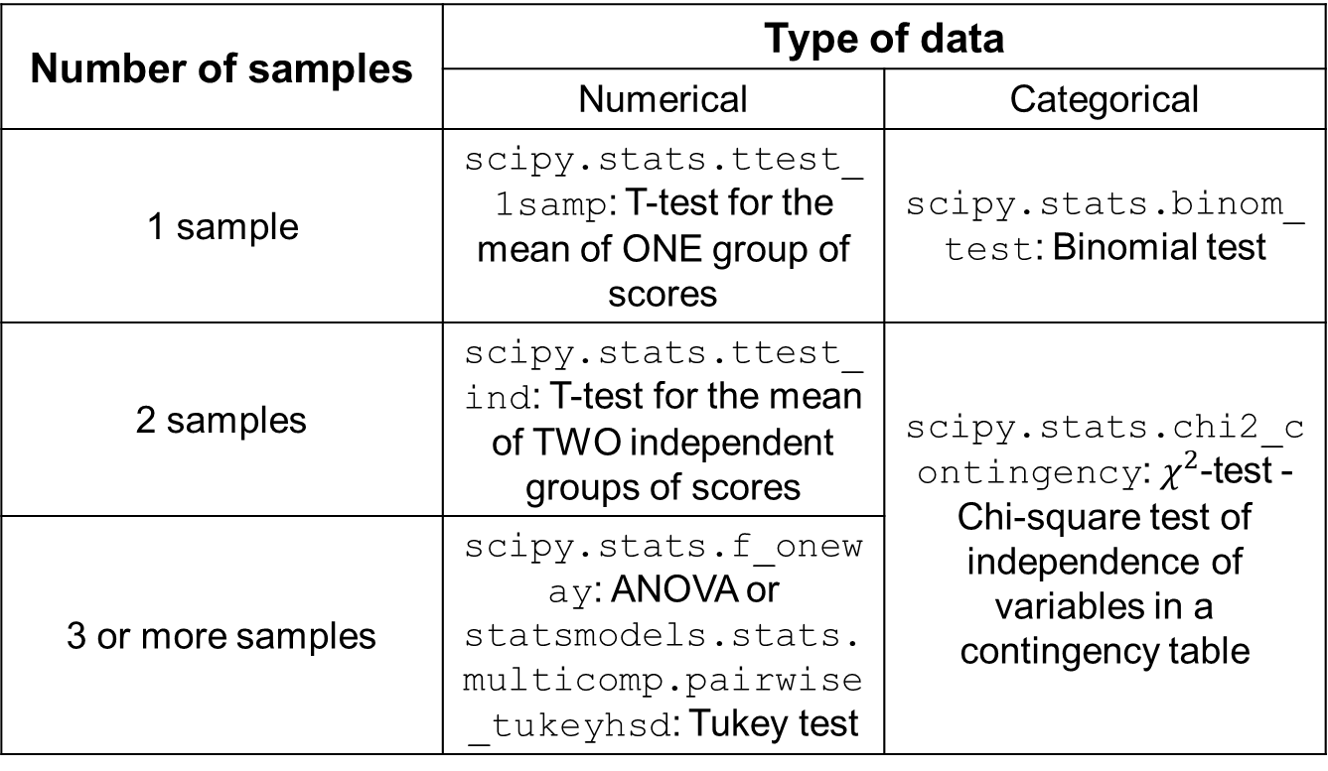

- Calculate the test statistic (aka perform the hypothesis test) - The choice of our test statistic depends on the type of problem at hand. Following is a useful grid that is a re-creation from Ref [4] below.

A majority of the time, however, we are looking at difference between two samples and hence are interested in using t-test for 2 independent groups of scores. An important point to note here is that by default, Student’s t-test assumes that the two population variances are the same. When this assumption breaks down, a modification needs to be made to use the Welch t-test instead.

A majority of the time, however, we are looking at difference between two samples and hence are interested in using t-test for 2 independent groups of scores. An important point to note here is that by default, Student’s t-test assumes that the two population variances are the same. When this assumption breaks down, a modification needs to be made to use the Welch t-test instead. - Make conclusions - The output of the appropriate test would be a test-statistic value (which is not all that relevant) and the p-value (which is lot more important). A p-value >0.05 suggests that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. If we are looking for difference in means, it is also useful to compute the confidence intervals. If we are interested in differences in means of the two samples, the confidence interval should not contain 0.

Other considerations -

There are many nuances that need to be considered which count as best practices when it comes to experimental design.

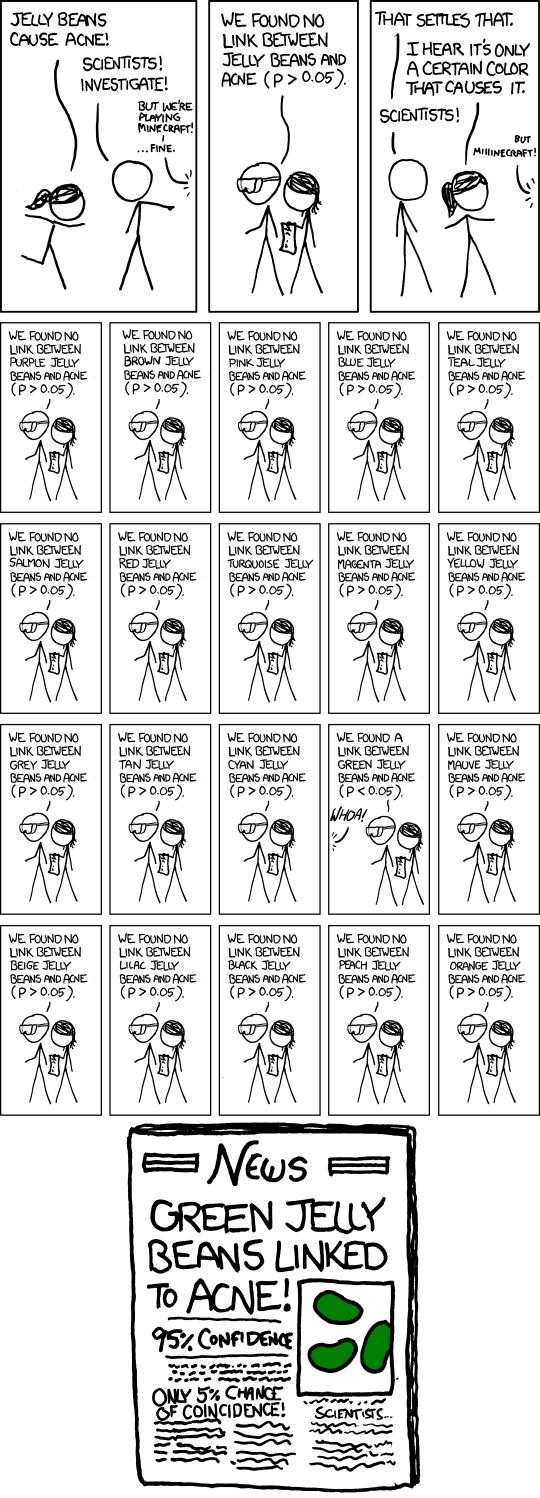

- The problem of multiple comparisons - The multiple comparisons problem occurs when a set of statistical inferences are made simultaneously. Consider a case when we have 20 different variants of an A/B testing setup. If we use the typical \( \alpha \) value of 0.05, there’s a 1/20 chance of getting a false positive. So, if we have 20 variants, we are almost guaranteed to observe an effect. See relevant xkcd comic below:

So what do we do in such cases? The natural way to solve this problem is to use a lower p-value. Exactly how much lower is estimated by what’s called a Bonferroni correction, which simply involves testing each hypothesis \( p_i \leq \frac{\alpha}{m} \), where \( m \) is the total number of hypotheses. It is worth noting that the p-value obtained from Bonferroni correction tends on the conservative side.

-

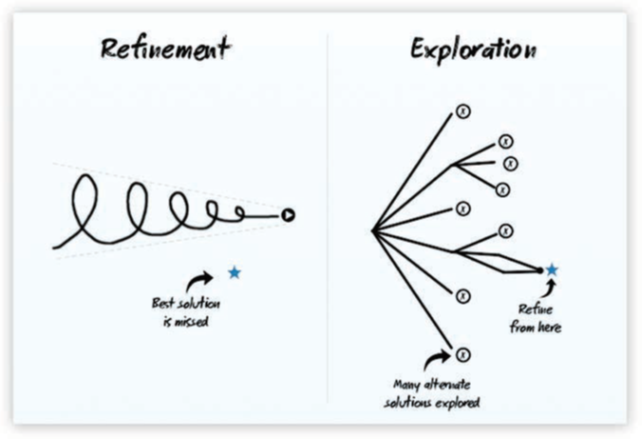

Exploration versus exploitation - aiming for the global optimum: The goal of an A/B test ideally would be to optimize between exploration and exploitation - the classic multi-armed bandit problem. Essentially, in the multi-armed bandit problem, we are using the allocated resources to optimize the exploration-exploitation trade-off. In the context of A/B testing, the idea would be to quickly identify the options that are profitable and pool more resources into these variants, thus eliminating the really ineffective choices early on. The above is similar to the recommendation by Dan and Pete -

The Refinement path might lead you to miss out on the best solution that could have been discovered with the Exploration approach. While refinement can lead to a solution better than what you have today, we recommend exploring multiple alternatives that might not resemble the current site first. We encourage the kind of humility and bravery required to say, You know, the website we have today is far from perfect. Let s try some dramatically new layouts, new designs, and redesigns, figure out which of those work well, and then refine from there.

- There is such a thing as too many splits: There are two potential drawbacks to having too many splits and hypotheses to test - firstly, you are effectively reducing the number of samples in each split (which wouldn’t be a problem for very large companies) and secondly, there is still the problem of multiple comparisons mentioned above. We have to refer to the popular Google experiment of trying 41 shades of blue at this point. Like the adage goes, just because we can do something, it doesn’t mean that we should.

- Rule of Three: This is a useful rule when we wish to extend our observations at the sample to the population - let’s say we conduct a randomized control trial (to test the effectiveness of a diagnostic test) on 200 subjects and they all turn out to be negative observations; we wish to come up with the confidence interval. In such a scenario, the rule of three states that if a certain event did not occur in a sample with n subjects, the interval [0 to 3/n] represents the 95% confidence interval for the rate of occurrences in the population. So, in the above example, we can state that the confidence interval for the effectiveness of the said test in the population is [0,3/200] = [0,1/67]. The Wiki article has a quick derivation of the rule.

- Good idea to start with an A/A test: In an A/A test, the experimentation layout is tested with two identical variants. This helps in achieving two goals - firstly, sanity checking to ensure that we do not see an effect and secondly, establishes a baseline variance (ie, empirical variability) for the data. On that second point, for instance, it helps to establish the variation in data over the span of an entire week before we venture into running our A/B test. If we observe a large variability in the A/A test, it’s an indication that the A/B might not end up yielding anything of value.

- A/B testing is not panacea: A/B testing is good for a lot of things, but not for everything. A/B testing is generally not useful when there are major layout changes to the platform. The novelty effect of the new layout leads to a lot of variability in the data that we obtain and no conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of the new design. Some ways to overcome this problem is to use more qualitative data, such as focus groups, surveys and retrospective studies.

References and further reading:

- A / B Testing: The Most Powerful Way to Turn Clicks Into Customers by Dan Siroker and Pete Kooman

- How Not To Run an A/B test by Evan Miller

- Some excellent scipy experiments

- Hypothesis Testing with SciPy - Hillary Green-Lerman - an underrated talk!

- Optimizely.com - a popular platform for commercial A/B testing.

- Udacity’s course on A/B testing