Workflows in Machine Learning

In the last couple of years, we machine learning practitioners have realized as a community the importance of focusing on not just the development of the algorithm/model itself but also the operations side involved in shipping the model. It is clear in hindsight that some level of integration between the conventionally disconnected, siloed responsibilities of DevOps Engineers, Data Scientists and ML Engineers was inevitable to facilitate better products. The dawn of so-called MLOps (Machine Learning Operations, à la DevOps) is an indication that the practice of data science is no longer treated as the wild west. It did not take us long to realize that developing a well-trained model was just a small fraction of the work, especially in a time with very robust machine learning frameworks (TensorFlow, Pytorch, XGBoost) - for further reading, refer to [1].

It is estimated that the composition of a mature machine learning system might end up being (at most) 5% machine learning code and (at least) 95% glue code [1]

https://twitter.com/ginablaber/status/971450218095943681

Why MLOps?

There are some important reasons why the operations aspects of the machine learning frameworks are not just relevant to the data engineers and developers, but also acutely pertinent to data scientists. Data drift and concept drift are two such reasons. Once a model is in production, there might be a fundamental change in the new data ingested into the model. Evidently, writing robust unit tests that check for changes in the schema are important, but new data might also prompt a fundamental change in the model that one might want to use. A similar argument applies to concept drift. The goal is to have a pipeline in place to be able to catch such drifts and make changes to the model. Like the saying goes, “a well-trained model is just the beginning”. Reproducibility/reusability is another strong motivation for robust MLOps principles and frameworks - ML models are notorious for not being reproducible due to a myriad of reasons (least of which are differences in data, differences in versions of libraries). Unsurprisingly Andrew Ng has lead the academic efforts of MLOps (here is an excellent introduction). Also, Martin Fowler wrote a great blog post on the topic of continuous delivery for machine learning.

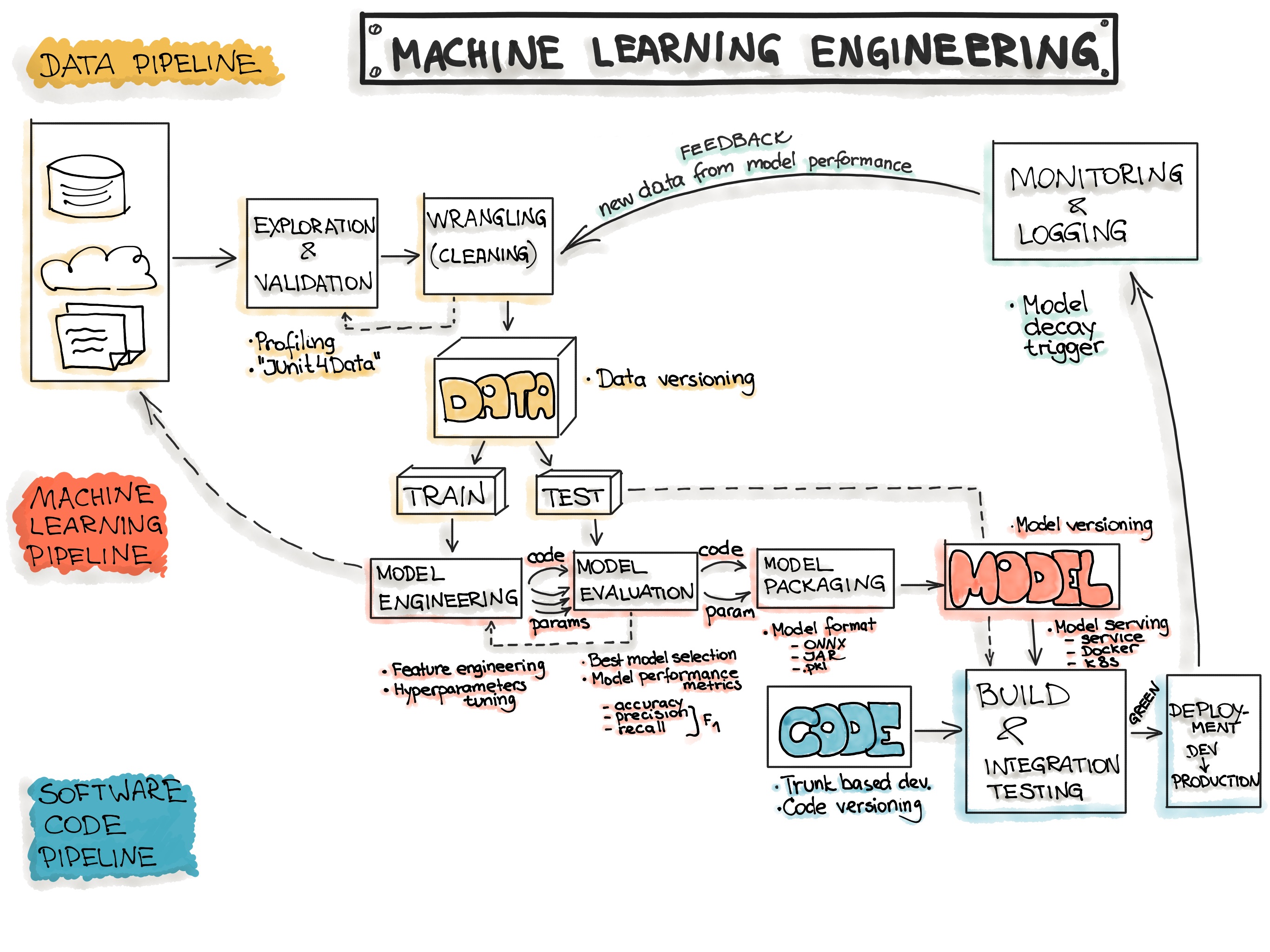

The architecture of the machine learning workflow has many components, drawing some parallels to typical DevOps frameworks but with several extra components. I will not attempt to reinvent the wheel here, but instead just borrow the workflow prepared by others:

Typical ML workflow (taken from [2])

It is often said that MLOps is a combination of DataOps, DevOps and ModelOps. There are lots of recent packages that help with different components of the MLOps workflow. In this blog post, we will explore some of those features and tools.

Tracking using MLflow

MLflow is an open source platform developed by Databricks for managing end-to-end machine learning lifecycle. MLflow is designed to be agnostic to the ML platform we intend to use. MLflow has 4 different components (MLflow Tracking, MLflow Projects, MLflow Models and MLflow Registry). We are only talking about the Tracking component here, which is an API and UI for logging parameters, code versions, metrics, and artifacts (artifacts are outputs of any kind) when running your machine learning code and for later visualizing the results. MLflow Tracking can be hosted either on a local server or a cloud provider.

The installation and usage of MLflow is straightforward (a quick pip install mlflow will get you going). A working training model will only need a few extra lines to access the tracking API and store parameters, metrics and other artifacts.

with mlflow.start_run():

if not os.path.exists("outputs"):

os.makedirs("outputs")

mlflow.log_artifacts("outputs")

mlflow.log_param("data_file", file)

mlflow.log_param("n_estimators", n_est)

mlflow.log_metric("RF_accuracy", acc_RF)

mlflow.sklearn.log_model(classifier_RF,'outputs')

Including just these lines will track runs with access to a neat UI as well. The UI can be hosted locally and accessed through mlflow ui.

The tracked model file includes a containerized folder with a pickle file, a config file and a requirements.txt. This is packaged well for easy model registry, which is another component of MLflow. All of this is ostensibly very useful during the experimentation phase.

Version control using DVC

DVC stands for data version control - DVC is a tool built on top of git to make ML models shareable and reproducible. When we are doing version control with data, we are clearly not adding our data to our github repo (that’s not what github is for!). DVC connects the data in your local repository to your cloud account, where it maintains a repo of your data. The key step is the inclusion of the data.xml.dvc file in the data directory of the repo, as shown in the https://github.com/iterative/dataset-registry/tree/master/get-started folder. The file looks like below:

outs:

- md5: a304afb96060aad90176268345e10355

size: 37891850

path: data.xml

Also, the data file itself (data.xml) is excluded from the git repository (through an entry in your .gitignore. Working with DVC can be seen to be analogous to working with git, where the git commands are replaced by your DVC commands whenever you are dealing with data. The set of commands to get version control going looks like the following:

dvc init

dvc add data/data.xml

git add data/data.xml.dvc data/.gitignore

git commit -m "Add raw data"

# The remote repository for the data can be any cloud

# provider

dvc remote add -d storage s3://mybucket/dvcstore

Alternatively, remote can also be set to google drive:

dvc remote add -d storage gdrive://<gdrive_tag>

where the <gdrive_tag> is the ID that’s at the end of the google drive URL. The remaining steps are similar to git commands:

git commit -m "Configure remote storage"

dvc push

CI/CD using GitHub Actions and CML

Continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) is an important DevOps concept, which is essentially the automation of building, testing and deployment of applications. This means that a change in the code automatically triggers an action (rebuilding and reevaluating the model). We will use GitHub Actions and Continuous Machine Learning (CML) by iterative.ai to enable CI/CD for our project. The usage of GitHub actions involves creation of a yaml file in repo/.github/workflows/cml.yaml. The composition of the yaml file is taken from the CML repo - https://github.com/iterative/cml#getting-started.

name: model-training

on: [push]

jobs:

run:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- uses: actions/setup-python@v2

- uses: iterative/setup-cml@v1

- name: Train model

env:

REPO_TOKEN: $

run: |

pip install -r requirements.txt

python train.py

cat metrics.txt >> report.md

cml-publish accuracies.png --md >> report.md

cml-send-comment report.md

Including this yaml file triggers a GitHub action every time changes are pushed into the repo. Moreover, CML generates a report for us with metrics and any visualization that we have. In essence, the Pull Request page will track the evolution of the model performance as we push more changes. An example report will look like the following -

Concluding remarks

The advent of MLOps and its subsequent rise in adoption popularity is an indication of the natural progression of the machine learning community and its maturity, an indication that there is more to shipping machine learning models than endless training with exceedingly sophisticated models. It is also a suggestion to incorporate solid software engineering concepts towards production of ML models. This was just an introduction; there are many more important components of the ML lifecycle that I will attempt to implement and write about in upcoming blog posts.

References

[1] Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems by D. Scully et al., NEURIPS 2015

[2] https://ml-ops.org/content/end-to-end-ml-workflow